Episode Transcript

[00:00:01] Speaker A: Elizabeth, how's it going?

[00:00:03] Speaker B: It's going well.

[00:00:04] Speaker A: All right. So, Elizabeth, are you ready for our, to begin our live listening journey?

[00:00:11] Speaker B: Yes, I am.

[00:00:12] Speaker A: Okay.

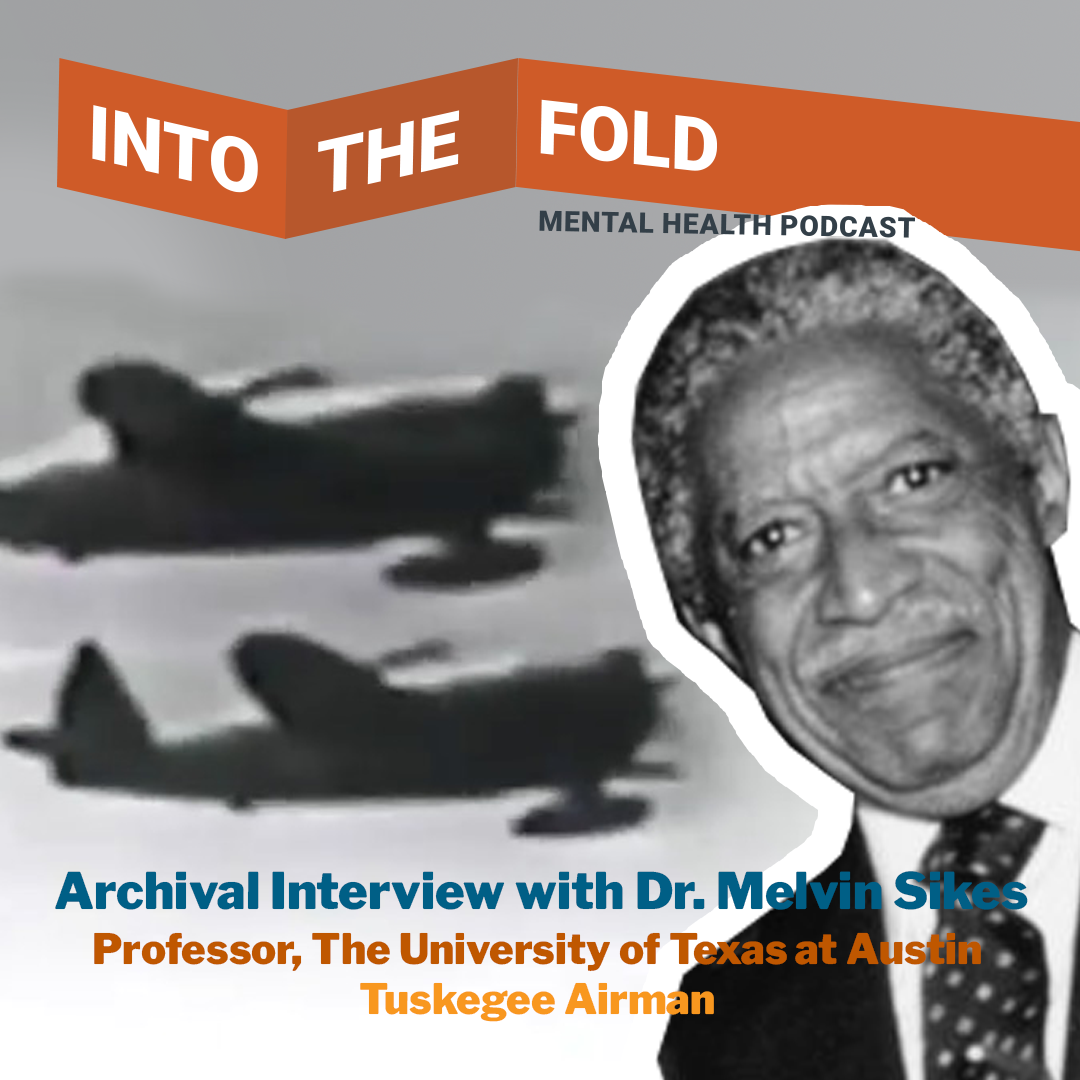

[00:00:23] Speaker C: From the University of Texas at Austin, this is how do you feel?

We're really going to help our students educationally, psychosocially, vocationally. We've got to be concerned about them as human beings, as persons, and we've got to help them develop a kind of pride that will relieve them of the need to use rhetoric instead of pride.

In cooperation with the Hogg foundation for Mental Health at Boston, this is another in a series of conversations about mental health projects funded in part by the Hogg foundation. Your host is Bert Kruger Smith, the foundation's assistant to the president for mental health Education.

[00:01:18] Speaker D: Studio guests are involved in an innovative project about which they will tell you. They are Dr. Mel Sykes, professor of educational psychology at the University of Texas at Austin and director of the center for the Improvement of Intergroup Relations.

With him are two of his graduate student staff, lurester Batiste and Sandy Chatham.

Mel, I think we will begin with you since the center is pretty much your baby. That's a very intriguing title, the center for the Improvement of Intergroup Relations. I think much of the world has been working on that. Let me ask you, what does the title mean according to your lights and program?

[00:02:05] Speaker C: I think we selected that title, Bert, to give us wide range. We envisioned doing so many things that we needed as wide range under some kind of rubric as we could find. And as you have said, we can do anything under this title and get away with it.

[00:02:22] Speaker D: What are some of the things that you envision?

[00:02:26] Speaker C: We have about four thrusts. One is research. We shall be concerned about researching our activities. And I might tell you something about our activities. We haven't said what we're really doing. We're concerned about relating the community here at the University of Texas at Austin, the community and the university.

We feel so often that persons feel that universities are not concerned about what's happening to the man out there in the field. We are, and we want to show that concern in the way that we can best do it, research being one way, whatever do out there.

[00:03:04] Speaker A: A rich Sonora's voice.

[00:03:06] Speaker C: We want to research to find whether or not we're really doing the radio ready or whether we're really meeting the needs of the public that we're trying to serve. Another thrust we're calling an enabling thrust. There are many wonderful community organizations that are doing great things, but many of them lack expertise in particular areas. For instance, so many people are concerned about economic development. They aren't aware of the fact that there are certain kinds of programs that can be funded by the federal government if proposals are sent to the right agencies. We feel it's our responsibility to help these people develop the proposals, to send those proposals forward, and then to aid in any other kind of way. That's a kind of enabling thrust where you give the community or the organization, that community an opportunity to do, quote, its own thing with your help.

[00:04:02] Speaker D: And you're talking so far about research and consultation.

[00:04:06] Speaker C: Right. All right. There's a third area, programmatic. We think certainly that there may be kinds of programs that we ought to initiate, so we'll be initiating programs that tend to relate community university. And lastly, we found that so often people are doing things and other people don't know anything about it. We've spent almost two years developing what we call a kind of data bank. What are the various kinds of programs in which we're related? Where are they located? What are they doing? This kind of data bank is a fourth thrust that we have.

[00:04:40] Speaker D: Mel Sykes, I know that you can't have.

[00:04:43] Speaker A: Okay, Elizabeth, so let's pick it up there.

So what have you been able to find out about what Mel is referring to? The center for the improvement of intergroup relationships. And if you haven't been able to find out a like, do you have any intuition about just what it ended up being?

[00:05:06] Speaker B: Yeah, I haven't been able to find out much about doesn't. I've searched in the finding aids for the university archives and other Texas archives, and it does not come up.

And I haven't been able to see it referenced in any research citations or anything like that. So I don't really know what happened with it or how far it got or how long it was around.

I can't confirm either way what happened with it, but I do know that its topic, which is on intergroup relations, was a really important topic in sociology at this time, particularly in regard to the civil rights movement. So the study of intergroup relations that grew tremendously following World War II and the civil rights movement of the led to social scientists to study prejudice, discrimination, and collective action in the context of race in America. So, for example, in 1952, the NAACP actually put out a call for social science researchers to study these issues in light of the Brown v. Board of Education lawsuit. And then also in 1967, MLK spoke at the annual meeting of the American Psychological association, and he urged social scientists to advance causes of social justice.

And in 1967, MLK spoke at the annual meeting of the American Psychological Association.

[00:06:46] Speaker A: I didn't know that.

[00:06:46] Speaker B: Yeah. And he urged social scientists to advance the causes of social justice in their research. So in his speech, he actually called on scientists to study many topics related to the civil rights movement, which included barriers to upward social mobility for black Americans, political engagement and action in the black community, and the processes of psychological and ideological change, which is very much in the wheelhouse of intergroup relations, which is what Mel was trying to do in this center.

[00:07:18] Speaker A: Okay, so we are coming at you from the vantage point of early 2024 at the University of Texas at Austin. There once was, and I guess we don't know how similar this is to the center for the improvement of intergroup relationships, but there once was a multicultural engagement center here at UT Austin.

There really is no longer.

And that has to do with.

I don't know how much this is actually going to go into the final cut, but I'm just saying it. This has to do with Senate Bill 17, which passed out of the Texas legislature last year, and the rather strict prohibitions on diversity, equity, and inclusion programs of various sorts now going into effect. And so for our listeners, as we continue to listen to this really fascinating interview from the early 1970s, you can be thinking about the current climate and whether it is even your sense that the things that they're talking about would even be possible today.

[00:08:51] Speaker D: I'd like to know who sponsors you and who houses you.

[00:08:56] Speaker C: It kind of came out of a brainchild, and I think that I have to give a lot of credit to Dr. Holtzman and the Hogg Foundation. Wayne and I were talking about, gee whiz, what can we do to bring the university closer to the community? And we decided, well, maybe some kind of urban studies center, but everybody was doing that. I talked with some other people within the department and then with some of my students. I have a class in cultural deprivation, and I guess everyone deserves credit for coming up with, well, let's develop a kind of organism rather than organization, if you want to call it, and let's start doing something. Then we came up with the name center for the Improvement of Intergroup Relations because we knew we would be interested in so many kinds of endeavors.

[00:09:41] Speaker D: There are other questions that we're going to want to ask, but at this point I would like to ask you, did these two young women grow out of your class in cultural deprivation?

[00:09:54] Speaker C: Yes, actually, there were three. We tried to make this a triethnic undertaking, and unfortunately, Miss Maria Martinez, who is another part of our staff, could not be here. But these two young ladies certainly grew out of that.

[00:10:07] Speaker D: Let me ask them some questions. Sandy Chatham, how did you get interested, other than being a member of this class of Mel's? I'm sure not all members of the class went into the center. What sent you into this kind of work?

[00:10:22] Speaker E: Well, I initially met Mel as he was my professor in that class, and we discussed quite a bit the racial ethnic problems that we're having. I am from a middle class white family and realized more in class how I'd been raised with somewhat of a middle class white attitude. I had very stereotyped feelings towards blacks and Chicanos. As I began to have contact with these people in my classes, I found that these attitudes that I had were, they were just not right, that my attitudes and the behaviors of these people weren't consistent at all. And I began to examine why I had these attitudes and really began to realize more how the white people really don't understand, don't know, don't have much contact with the other ethnic groups. Our attitudes are just all wrong.

[00:11:25] Speaker D: You moved in and got increasingly committed. You have stayed in the program.

Is that sense of commitment what the thing that made you stay on after the class was over?

[00:11:39] Speaker E: That and our staff members, we've really grown to have a tremendous liking for one another. We work very well together, and it just seems that there's such a tremendous demand to work out intergroup problems that there's always more work to be done.

[00:12:01] Speaker D: Sandy, now that you have graduated, you have another job, I believe, in addition to this, what are you doing for a living?

[00:12:09] Speaker E: Say I'm a case worker at the Austin State hospital.

[00:12:13] Speaker D: But you are keeping up your interest and concern in the center.

[00:12:17] Speaker E: Yes, this is pretty much volunteer at this time.

[00:12:23] Speaker D: There have been so many discussions about the facts of isolation and alienation, the feelings which are part of severe cultural deprivation and also part of people who suffer from mental illness. I'm wondering whether philosophically, in a sense, you see a tie in between your casework at the hospital and your work at the center.

[00:12:50] Speaker E: Yes, I do. It seems that most of our patients that are from minority groups, the color, their ethnic group has a tremendous amount.

[00:13:10] Speaker B: Of.

[00:13:12] Speaker E: It, is very much concerned with their illness. I would say I have had patients that would not relate to me at all because they were black and I was white and could not understand that I would be the least bit interested in them. I just recently had a patient who would not even speak with me until we discussed the possibility of going out and getting a job. And we spent an entire day riding the bus and going from place to place, applying for jobs. And she was just astounded at the end of that day that someone was actually interested, and especially a white person, to help her get out of the hospital. And just came out point blank and asked me, are you really concerned about Elizabeth?

[00:13:54] Speaker A: It's just so fascinating listening. I don't know if it's her. I figure she's quite young, this student, if it's her accent that's throwing me, but she sounds kind of seasoned at the same time.

When I was listening to this, I was just very struck by, you know, the things that she's talking about regarding her own personal learning curve, about when it came to race. That was sort of kick started by her involvement with this group.

[00:14:30] Speaker B: Right.

[00:14:33] Speaker A: I don't know just what thoughts occurred to you when listening to that part and how it kind of relates to today's climate, because we still see that kind of thing talked about a lot.

[00:14:49] Speaker B: Well, it seems like moving away from home, going to college, meeting new people, getting exposed to different ways of thinking, really contributed to her development as a person and expanded her worldview. And I think that is something that is still the case for a lot of people who might grow up in more isolated communities where they're not interacting with people of different races or cultural backgrounds as often or at least know that they are.

And so that pivotal learning experience in that, I still see that with folks today.

[00:15:41] Speaker A: Okay. Yeah. And then she mentions her work at Ash, which is interesting.

And, I mean, I don't think people were using this word back then, but, like, intersectionality, I can only imagine. And I don't know if she grocked this at the time, but for someone to have been having the kind of experience that she was having from having taken Mel's class, from being involved with this center, for all we know, it could have been a great boon for Austin State Hospital to have someone, even just a volunteer with that kind of, I guess, embryonic, intersectional experience.

And you yourself are kind of. You've become deeply involved with Austin State Hospital, its work on archiving and preserving.

And I don't know, does any of this sort of bring up anything for you from your own experience doing that? Kind of.

[00:17:03] Speaker B: Know, it would be fascinating to find her today and interview her for our oral history project about her experiences working as a case worker at the Austin State Hospital in the kind of support that maybe she had to provide this complex and necessarily intersectional care to patients at the hospital, especially as a young woman, just learning about all of these differences in the world. Well, this would be a time when peer support was not really a concept necessarily.

[00:17:53] Speaker A: Sure. Yeah.

[00:17:54] Speaker B: Because that's something that arose, was maybe starting to arise in the consumer and peer community, but was not widespread in the mainstream.

[00:18:06] Speaker A: Yeah.

Okay. So we return now to our human conditioning conversation and just see what more we can learn.

[00:18:17] Speaker D: Lou Esther, let me ask you some questions about what brought you into the center and kept you there, in a sense.

[00:18:25] Speaker F: Well, it's pretty much like Sandy's, really. I met Mel in his class. He was my professor. While I was there in his class, he tried to get us involved in different things that were going on in the community.

To start with, I joined the breakfast program, which is now the community united front.

[00:18:46] Speaker D: Excuse me, Lou Esther, this breakfast program is for whom?

[00:18:50] Speaker F: It's for children, the poor, or if you want to call it, economically deprived children. And this is black, brown and white. I joined the program at least the first time I went over there. I felt rejected by my own people because I was just sitting there. Nobody knew me. They were very cold toward me because they didn't say anything. It didn't seem as if they appreciated my being there. And really, I didn't feel needed because there were quite a number of them there that particular morning. But it just so happened that same morning, Mel came over and I told him I wasn't going to come back to the program. And he suggested to me that I should stay because this was one thing that he wanted to do in the center to research the kids, find out how the breakfast program was, helping them, seeing if their grades were going to be improved, and so forth.

[00:19:42] Speaker A: Okay. So, Elizabeth, you have some tidbits for us that may relate to some of the things that Lewester was just sharing?

[00:19:50] Speaker B: Yes. So I just wanted to mention the breakfast program that she talks about, hosted by the community United Front.

So I found this pretty interesting. But the community united Front was a black power organization in Austin, Texas, and in 1971, so just a year before this radio program, a year or two before it, they leased six billboards around east Austin protesting the segregation of Austin's black and brown population and the lack of services that were provided to them in East Austin. So these billboards really highlighted the bleak living conditions in the area. And they said things like, welcome to East Austin. You are now leaving the american dream. And they warned residents and tourists, beware of rats, roaches, and people with a lack of food, clothing and jobs. And so they were pretty blunt about the situation of segregation in Austin, and they weren't totally well received by everybody in the community. Right.

But they did lead to many private donations, and those donations actually helped support that breakfast, that free breakfast that Lou Esther is talking about, and also a daycare program for children and a job training program and a medical clinic for black residents and low income Austinites. So I just thought that was an interesting tidbit of local history.

[00:21:24] Speaker A: Yeah. And so just to be very clear, we are taking a look back into not only a particular moment in the history of, I guess, our reckoning with race and mental health, which this kind of is, but also just a look back at the prevailing mood, the prevailing vibe at the time around campus.

[00:21:53] Speaker B: Right.

[00:21:53] Speaker A: There was much stuff like this afoot going on can make a guy today a little bit envious, even.

And so, yeah.

Thank you for providing that bit of context, Elizabeth. Okay.

[00:22:21] Speaker D: Have you so far had any parents interested in coming in?

[00:22:25] Speaker C: Yes, we have. We've had several parents to call and say, what can we do?

There have been so many things they could do. It's been difficult for us to point out any specific things, but we have had that kind of interest by parents. And we're glad because, as Lester implied, we didn't want parents to feel that here's another revolutionary movement simply because we're getting students together. It's hopefully a growth, understanding movement. And this has another thing to it, too. Bert. We hear so much about parents not working with students. We hope that we can interest all of the parents of all of these students to draw them closer to the students and maybe get rid of some of the problems that we're seeing between parents and students, this age gap and all this kind of thing that we hear about.

[00:23:13] Speaker D: You're not only talking about the intergroup, intercultural, but the generation gap, too, right? Very good, Mel. One of the major thrusts of your center from our discussions is the bringing together of top black professors in a congress for black professors in higher education.

This is an important move, and I wonder if you could tell us what prompted the initiation of such a congress and what you hope will happen in the future.

[00:23:45] Speaker C: This grew out of some of my own frustrations, some of the kinds of things that I heard other black professors talking about. For an example, we heard a lot about the brain drain, the matter of siphoning off top black professors from black institutions, bringing them to white institutions. Many of us began to wonder, where do we really belong? Should we be in this white institution, or should we be in the black institution? Where can we best give our services? What ought we be doing? But it seemed that no one was doing very much about this, but sort of commiserating with each other or wallowing in anguish.

I felt that we ought to get together nationally and take a look at this because this not only affected us, but it had to affect what we meant to our students, black, white, brown, whatever, because if we were using energy, struggling with this, worrying about our places, that was energy that we ought be using in teaching.

So again, I talked with Wayne. I owe so much to hog foundation for assistance, for support, so many things that I really want to do, and I say this very sincerely. Talked with Wayne about this and he said, well, why don't we do something? What do you want to said, let's see if we can get some top thinkers from all over the country. We know we'll miss a lot of people, but keep it limited and struggle with at least five areas with which education itself is concerned.

[00:25:20] Speaker D: What are the five areas now?

[00:25:22] Speaker C: We're concerned about research for one area. Go back to research again.

You see, we as black professionals have said so often that tests like the SAT, the GRE, discriminate against minority groups. We know this. There has been some proof that this is true, but we continue to use these tests. It seemed to me that if we say that these tests discriminate, we as black professionals ought to come up with tests or with items that didn't discriminate recently. I call this a professional, self help sort of situation.

There are many other areas in this whole matter of research that we feel we ought be doing for minority group people. I don't think it's because the Anglo can't. There are many things he doesn't understand. He just doesn't have the experience. And if we are saying this is true, then we ought provide that experience. We ought to work with our colleagues, and then we wouldn't have the problems with Jensen and others that we've been fighting with. Another area, of course, is community work.

Here we are at our universities.

Usually the university will say, we hired you not because you're black, but because we want you to do a particular job. There's some truth in it. There's some not truth in that. The point is, for those of us who are hired because we are, quote, pretty good in a particular area, still are going to have to be concerned with minority group problems. We're still going to be called upon by both community and university. Now, what about our loads and what responsibility do we have in the community? And this is a terrific drain upon us. Should we expect, be expected to carry out the same functions that any other professor carries out, do all that we're doing, extra, et cetera, et cetera. What's our position on that kind of thing?

[00:27:14] Speaker A: Honestly, Elizabeth, I think the post sb 17 world would drive this man crazy.

Yeah.

He's just very blunt, very plain spoken. Yes, but he was still at the front end talking about the center and this sense that because we don't want to scare parents.

And again, it just sounds very much like the rhetorical dance that we're now doing about the language that we choose to describe ourselves.

So underserved communities, rather than something else.

[00:28:02] Speaker B: Not to appear too revolutionary.

[00:28:03] Speaker A: I think he had some of his own words, like we're being.

That are softer edged than revolutionary.

[00:28:12] Speaker B: Well, and this is the 1970s, which is coming out of a very tumultuous time.

[00:28:19] Speaker A: Right? Yeah.

But then after that, he starts talking about what the first National Congress of black professionals in higher education, which you even wrote a blog post for us about. And so perhaps you could just give us just a little bit more kind of context about that and about the Hog foundation's level of involvement and what its goal was.

[00:28:54] Speaker B: Yeah, I mean, it was really a pretty spectacular convening, looking back at it now.

But it was the largest grant that the Hog foundation gave out in 1972. So it was a significant investment from the Hog foundation.

And our president at the time, Wayne Holtzman, he spoke at it as well. But I think it's very important to note that former president Lyndon Bean Johnson gave the opening speech for it. So they were able to get a lot of really big names at this conference. And this was just a year before LBJ died.

[00:29:43] Speaker A: Right.

[00:29:44] Speaker B: So it's one of his last speaking engagements, for sure.

But they really gathered a lot of important people around the country to talk about the issues surrounding, or to talk about the issues about what it means to be a black professor or student in a predominantly white institution like the University of Texas at the time.

And they had people. Some of the participants included Althea Simmons, who was a civil rights activist and attorney with the NAACP for over 35 years.

Dr. Owen Knox. He was an educator who dedicated his life to advancing the quality of education in the black community in Los Angeles. He has a school named after him there, Dr. Elias Blake, Jr. Who helped create the upward bound program, which Lou and Burt mentioned this program earlier, that it is a federal program aimed at recruiting low income and first generation college students. And Dr. Elias Blake, Jr. He also advised two presidents, President Nixon and Carter, on the needs of black students in higher education. And those are just a few names that I looked into when I was going through the program and all the proceedings that were written up afterwards. There were a lot of really big thinkers at this conference.

[00:31:26] Speaker A: Yeah, it's pretty amazing.

I'm only just now learning about LBJ's appearance at that.

Very interesting.

A lot of what Mel is talking about is black professors kind of helping to bridge the gap between school and community.

It's very interesting to hear him talk about, and I'm trying not to put words in his mouth, but his sense that he never uses the word token, but his sense that his academic credentials might not be the only reason why that he and others like him were hired.

[00:32:18] Speaker B: Right.

[00:32:19] Speaker A: And even sort of this wariness, this sense that in addition to my typical academic duties, that maybe, perhaps they're hoping that I will help them solve some of their black problems.

[00:32:35] Speaker B: Right.

[00:32:40] Speaker A: I'm sure that different versions of this come up a lot in this whole conversation about service on campus and how, what, besides my actual job duties, how much am I going to be giving back? How much am I going to be?

In a typical case, let's say it is like an academic of color.

A part of them wants to just hurl themselves into it. But then I think just as typically, they come to realize how exhausting it is.

And it sounds like that Mel is really voicing some of that.

[00:33:28] Speaker B: Well, he did a lot of research on what the experience of black students in predominantly white institutions were like. And so I think he was particularly sensitive to that dual cultural tension that pulls him from. I'm here to get a quality education that gets me further in the world while also being in this environment that's not very welcoming or understanding of where I'm coming from.

And if you read the reports from the conference that he and the Hog foundation hosted, one of the things that they mention is that black administrators and faculty need to be able to focus on the needs of black students rather than simply acting as, and this is a quote, squelters of unrest. Right?

[00:34:28] Speaker A: Yeah. Right.

[00:34:29] Speaker B: Very to the point.

[00:34:31] Speaker A: Right? Yeah.

[00:34:33] Speaker C: Okay.

[00:34:34] Speaker A: I think maybe we'll do maybe one more segment.

[00:34:40] Speaker C: Another area that we're concerned about is curriculum. We've complained about curriculum, and rightfully so. We think with the students that many of the curriculum offerings are totally irrelevant. And I think the teachers do too. But we're saying if we complain again, what do you have to offer as a solution, particularly teacher education? We've got so many well meaning student teachers, as we say, tripping about, stumbling over themselves and over their own ignorance and really hurting minority group people because they don't understand. And, you know, many have been frightened out of the field. There are so many who stuck their toe and it was too hot, and, boy, we just can't get them.

We feel that as black professionals, we ought to help bridge that gap between what the teacher is being taught and between what the teacher really faces when he gets out there in the field, particularly in times like these, when everything is emotionally laden, when parents are getting into fights over what ought to be the busting desegregation. This is a rough time, and we feel that we ought to, ought to be doing something about that.

[00:35:47] Speaker D: All three of those would keep you busy. Now you have two more.

[00:35:50] Speaker C: Yeah, that's right. One administration. We have a black president of a predominantly white school, Michigan state. Of course, I have teased and said that we're in a sophisticated carpet bagger situation again, that we're now grabbing up blacks, throwing them into things. Fortunately, this is a very good man and he can do a tremendous job. My concern is that we see this happen, then we look around for other black persons to be presidents, and we get people who might not be qualified, and we put them in because we think we really should. We think that we ought have internships and the like for blacks in predominantly white institutions, so that if there are things we don't know, we can learn, or that our black presidents, who may become presidents of predominantly white institutions ought. And, you know, you just might have a few white presidents or predominant black institutions, too. We would hope that would happen. So the whole matter of administration is of concern to us. And lastly, student personnel and student development. Now, if we're really going to help our students educationally, psychosocially, vocationally, we've got to be concerned about them as human beings, as persons, and we've got to help them develop a kind of pride that will relieve them of the need to use rhetoric instead of pride.

[00:37:11] Speaker D: While you're talking about the students, I'm going to turn back to these two young ladies who are very much a part of this center.

Lou Estre Batiste, let's start with you. Have you found from being a part of the center and some of this intergroup learning that has been taking place among you, have you changed your own personal attitudes and feel that you've been able to influence anybody else?

[00:37:39] Speaker F: Yes, I think I have, because I think about when I first came here to UT, I was a different person, and I became aware of blackness after I got here, because it seems that when you become a part of a white world almost predominantly. I mean, the total white thing, then you change. And so when I found myself, I found I was able to help other people. I think I've been able to help older people. We sometimes say when you're over 30, you in that generation gap. But I don't think that's necessarily true for black people because discrimination knows no age. So I try to help the over 30 group, the under 30. I try to reach everybody to try to make them proud of being black. And I think much of this has come from my being in the center to help.

[00:38:32] Speaker D: Let me ask that question a little bit further. How about Chicanos, Anglos?

[00:38:39] Speaker F: Have I helped them?

[00:38:41] Speaker D: Do you have a different feeling toward them in addition to a different feeling toward yourself and other blacks?

[00:38:46] Speaker F: Right. The thing is, well, I felt pretty inferior about being black until I got here and I got to know whites, let me say. And after I got to know them, I realized that they were people just like me. And Chicanos are some people that I never knew in Louisiana, because it's mostly, see, but after I got here, well, I got to know them as a different race of people. I used to see them, but I thought they were white.

So I think my outlook has totally.

[00:39:22] Speaker D: Changed with Sandy Chatham as an anglo middle class person.

How have you changed in attitude or been a change agent for others?

[00:39:34] Speaker E: Well, initially in the class that I had with Lou, Esther and Mel, my attitudes changed very. I went from overdoing and trying to be accepted by everyone until I reached a point where I realized that you just have to be and people will accept you for what you are or they won't. And so this has been my big change, is just trying to be, as opposed to knocking yourself out to be something you're not.

[00:40:03] Speaker D: Have you found changes within your own family as you've visited with them since these experiences?

[00:40:10] Speaker E: I hope so.

I see my role very much in working with the white people. It's so much easier, it seems to everybody wants to go into the minority communities and work there, but it is where the work is really needed, is in the white community, which is extremely difficult.

[00:40:33] Speaker D: Mel, I've heard you mention that out of this center there have been some spinoffs which might not be written down in the curriculum. But would you tell us one of the spinoffs that you mentioned earlier, we.

[00:40:47] Speaker C: Have had students to come in who are very much interested in a variety of kinds of community activities.

One young man was interested in police community relations, went out and did a tremendous job of researching this whole area, trying to find out where the difficulties really were in Austin. Bringing this back and that has helped the police. Another was interested in noise, by the way, noise pollution. He sent that to city hall, and in that particular situation, they're doing something about that. And all of that was sort of spin off activities where students have said, I want to do something. And I said, well, do whatever you want to do. Just so it relates to helping the community. There have been a number of these.

[00:41:26] Speaker D: And now is this center open to everyone? Could anybody come to you and say, I'd like to be a part of it? What would happen?

[00:41:34] Speaker C: Well, I would go crazy.

That has been happening. Sincerely, the center is, quote, open.

We're hoping that more students, more faculty members will become involved and that we can give viable service to the community. And it's open in this kind of way.

[00:41:51] Speaker D: Thank you very much, Dr. Mel Sykes, Lou Estre Batiste, and Sandy Chatham for appearing in this performance of how rhetoric instead of pride.

[00:42:04] Speaker A: Yeah, I wonder what he's getting at there, because I kind of think I know where when a student doesn't feel supported, I think there's a tendency, I don't know if he's talking specifically about black students to kind of want to puff themselves up with rhetoric instead of, you know, like the, the kind of, the kind of like actual resilience that is sort of sort of bolstered by just a real confidence that you belong, if that in any way makes sense for you.

[00:42:56] Speaker B: Yeah. I understood pride as being about, know, really having that foundation.

[00:43:03] Speaker A: Right. Yeah.

Is there anything else, Elizabeth, since we have you here, that might be useful context for this period of time that we're dropping in?

[00:43:23] Speaker B: Know, this was also at the same time as the Hog foundation was also embarking on a multi year project in Crystal City down in south Texas, to provide services and support for the mexican american population there. So this support for black and brown Texans was a priority for the Hog foundation in the 1970s, and it worked and looked a little differently than perhaps we would do it today.

[00:43:59] Speaker D: But.

[00:44:03] Speaker B: How far back and deep the concern of the hog foundation has had for the mental health of all Texans is always inspiring to see.

[00:44:14] Speaker A: All right, Elizabeth, thank you so much for taking the time, on a Friday, no less, to visit with us, to drop some knowledge for our listeners. We really do appreciate you.

[00:44:27] Speaker B: Thank you for having me.